THE SILK ROADS FROM THE PAST

TO THE FUTURE AND

THEIR INTERACTIONS WITH THE

FOREIGN TRADE OF TURKEY

CONTENTS

Abstract/Özet

Introduction

1. The Historic Silk Road

1.1. History of the Silk Road

1.2. Commercial Structure of the Historic Silk Road

2. The Modern Silk Roads

2.1. Birth of the New Silk Roads

2.2. International Initiatives and the New Silk Roads

2.3. Commercial Potential of the New Silk Roads

3. The Silk Roads and Turkey

3.1. The Role of Turkey in the Historic Silk Road

3.2. The Role of Turkey in the New Silk Roads

3.3. The Impact of the New Silk Roads on Turkeys Foreign Trade

Conclusion

Bibliography

Abstract

Transportation is a major factor in trade. Commercial activities can be

increased in parallel to improvements in transportational infrastructure. The

Silk Road functioned in this manner historically and played a paramount role in

the development of international commerce. In this context it proved vital in

the execution of intensive commercial activities, initially between Asia and

Europe, and later in Africa. Although the Historic Silk Road lost its

significance in the late 17th century, it is currently being revitalised. In

this context economic and political collaboration between nations is sought

through a variety of initiatives - the so-called New Silk Roads. Major among

such initiatives are oil-natural gas pipeline projects (OPP-NGPP), Transport

Corridor Europe Caucasus Asia (TRACECA), the Northern Distribution Network

(NSR-NDN), the Trans-Korean Railroad with the Trans-Siberian Railroad

(TKR-TSR), and the Gulf-Asia Model: Turkey is actively involved in most of

these. In this paper, brief information about such initiatives is offered and

their de facto and potential effects on the foreign trade of Turkey revealed.

Data show that such initiatives (excluding the TKR-TSR and the Gulf-Asian Model

due to their distance) have positive effects on Turkeys foreign trade.

Key Words: The historic silk road, The

new silk roads, Oil-natural gas pipeline, Transportation, Foreign trade.

GEÇMİŞTEN GELECEĞE İPEK

YOLLARI VE TÜRKİYENİN DIŞ TİCARETİ İLE ETKİLEŞİMLERİ

Özet

Ulaştırma, ticaret faaliyetinin temel unsurlarındandır. Şayet ulaştırma

imkânları gelişmişse ticarî faaliyetler de buna paralel olarak artırılabilir.

İpek Yolu da tarih boyunca bu fonksiyonu icra etmiş ve uluslararası ticaretin

geliştirilmesinde önemli bir rol oynamıştır. Bu kapsamda Tarihî İpek Yolu, önce

Asya ve Avrupa daha sonra Afrika kıtaları arasında kara ve deniz yoluyla yoğun

ticarî faaliyetlerin icrasına imkân sağlamıştır. 17.yüzyılın sonlarında önemini

kaybetmesine rağmen, Tarihî İpek Yolu, bugün farklı formlarıyla canlandırılmaya

çalışılmaktadır. Bu çerçevede, uluslar arasında Yeni İpek Yolları adı altında

birtakım inisiyatifler vasıtasıyla iktisadî ve siyasî işbirliklerine

gidilmektedir. Bunların başlıcaları petrol-doğalgaz boru hattı projeleri

(PBHP-DGBHP), Avrupa-Kafkasya-Asya Ulaşım Koridoru (TRACECA), Kuzey Dağıtım Ağı

(NSR-NDN), Kore-Sibirya Demiryolu (TKR-TSR) ve Körfez-Asya Modelidir. Türkiye

bunların önemli bir kısmında fiilen yer almaktadır. Bu çalışmada, söz konusu inisiyatifler hakkında kısa bilgiler verilmekte ve

bunların Türkiye dış ticaretine fiili ve muhtemel etkileri ortaya konmaktadır.

Veriler göstermektedir ki bu inisiyatifler (uzaklıkları dolayısıyla TKR-TSR ve

körfez-Asya Modeli dahil edilmemiştir) Türkiyenin dış ticaretine olumlu

etkilerde bulunmaktadır.

Anahtar Kelimeler: Tarihî ipek yolu, Yeni ipek

yolları, Petrol-doğalgaz boru hattı, Ulaştırma, Dış ticaret.

Introduction

As both an iconic symbol and a source of wealth, silk was important as one

of the most valued products carried on the interconnecting routes between continents.

Thus, this internationally desirable product played a significant role in the

establishment of relations between countries, while its name became

inextricably linked with the routes along which it was transported from the

second century BC to the late 17th century. At that point its value diminished

with the rise of new methods of transportation; roads, railways, and seaways.

The 19th century saw a resurgence of interest in the history and potential use

of the Historic Silk Road and its peripheral regions. With the exploration for

oil and natural gas reserves -which involved much of the world in the search

for potential collaboration with source and other user countries- the concept

the Modern Silk Roads or the New Silk Roads, in the sense of their

revitalisation, was born. The context being different, however, the term the

New Silk Road contains several meanings depending upon the

views/aims/projections of the countries and/or country groups on the region.

Many international initiatives have been launched with the aim of

benefiting from the resources located in the centre of the Historic Silk Road

Region. The most important of these are the so-called Asian Silk Road [oil and

gas pipeline projects (OPP-NGPP)], the European Silk Road (TRACECA), the

American Silk Road (NSR-NDN), the Korean-Russian Silk Road (TKR-TSR), and the

Gulfian Silk Road (the Gulf-Asia Model). The main factor for the establishment

of the said initiatives is the presence of oil and natural gas. Turkey is

involved in most of such initiatives in terms of the economic and political

aspects. In this paper, the New Silk Roads on the routes of the Historic Silk

Road are studied and their potential for the countries involved, particularly

Turkey, is revealed. In this context, de facto and potential effects of these

initiatives are studied in terms of Turkeys foreign trade. The data gathered

show that the effects of such initiatives are positive.

Material and method

This is a desk study, materials for which are books, articles, and statistics.

The paper consists of three sections. The first of these is a brief history of

the Silk Road and its commercial structure. The second is on current

international initiatives on the Historic Silk Road, namely the New Silk Roads

and their commercial potential. The last section includes the role played by

Turkey with regard to both of the above in the Historic and New Silk Roads. In

this context, the impact of the New Silk Roads on Turkeys foreign trade is

studied.

In order to demonstrate the effect of such initiatives on Turkeys foreign

trade, all countries were classified according to their involvement in the

projects. In this context, by using the crude oil transportation data of

2002-11 gathered from the Petroleum Pipeline Corporation of Turkey (BOTAŞ) and

foreign trade data from 1996-2012 provided by the Statistical Institute of

Turkey (TÜİK), the de facto effects of currently active projects i.e. the

Kerkuk-Ceyhan and Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan Crude Oil Pipeline Projects (COPP)

and the potential effects of other international initiatives (excluding TKR-TSR

and the Gulf-Asian Model due to their distance) i.e. Natural Gas Pipeline

Projects (NGPP), Transport Corridor Europe Caucasus Asia (TRACECA), and the

Northern Distribution Network (NDN), are found to be positive for Turkeys

foreign trade.

1. The Historic Silk Road

1.1. History of the Silk Road

The Historic Silk Road flourished for approximately 1,700 years as the most

important network of trade routes in history.[1]

These were proclaimed as the road of silk (Silk Road) by the German geologist

and geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen in his 19th century book China.[2] However, it is also said

that the term Great Silk Road was first coined by Cjan Syan, a Chinese

traveller who lived in the pre-christian era.[3]

Following the collaborative construction of the Karakorum highway between China

and Pakistan in 1980, German researchers concluded from their excavations in

the region that the Historic Silk Road had not, in fact, been constructed by

the Chinese but had already been in use by tribes prior to the coming of the

Chinese, who eventually used this road as a part of new intercontinental

trading network; initially for the silk trade and later for other activities.[4]

The term Historic Silk Road describes a series of trading networks that

facilitated the transfer of goods between Western markets in the Middle East

and Europe and Eastern markets, primarily in China. While the Caucasus mountain

passages and the Central Asian steppes were major obstacles to trade and

travel, there were, however, great oasis cities serving as way stations along

the route.[5] Changan, currently known as

Xian in China was the starting point of the journey. The caravan route then

divided into the North Road and South Road as it crossed the Western Territory

and met commercial roads in Rome.[6]

The main land routes of the Silk Road in B.C.150 were as follows:[7]

·

Changan-Yümen Kuang-Dun Huang-[Hami-Turphan (north route) or Karaşar

(middle route) or Loulan (south route)]-Kuça-Aksu-Kashgar-[Semerkand-Buhara

(north route) or Baktra (middle route) or Yarkent-Baktra (south

route)]-Merv-Schahrud-Hamadan-Palmyra-Antakya-the Mediterranean-Puteoli-Ostia-Rome

·

Changan-Yümen Kuang-Dun

Huang-Miran-Endere-Niya-Hotan-Yarkent-[Kashgar-Semerkand-Buhara (north route)

or Baktra (middle route) or Kashgar-Baktra (south

route)]-Merv-Schahrud-Hamadan-Palmyra-Antakya-the Mediterranean-Puteoli-Ostia-Roma.

During the Asian Hun State period, from the second century B.C. to the

fourth century A.D., there were three major routes on the Silk Road: the north,

middle, and south: [8]

·

North Route: Turphan-Urumchi (Urumçi)

·

Middle Route: Kurla-Kuça-Kashgar

·

South Route: Çarklık-Kashgar

·

West to East Route: Antakya-Syrian ports-Tigris and Euphrates

Reservoir-Caspian Sea-Balkh(Belh)-Pamir Plain-Kashgar-Hotan

·

A further important road to the East passed through the Caucasus and south

of the Caspian Sea.

According to another source, the routes of the Historic Silk Road were as

follows:[9]

·

North Route (depicted by Herodotus in B.C.450): Don River-Parthian

Region-Kansu (west of China).

·

South to East (estimation): Mesopotamia Region-Antakya and Gaziantep (Anatolia)-Iran-Pamir

Plain.

·

South to West (estimation): Gaziantep and Malatya (Anatolia)-Thrace

(Trakya)-İzmir (Aegea).

·

South Route to West (estimation): Trabzon and Sinop (Black Sea)-Alanya and

Antalya (Mediterranean)-Europe.

·

West to East Route (multimodal): A combination of Egyptian and Mesopotamian

Routes-Barygaza (a port city on Indian Ocean).

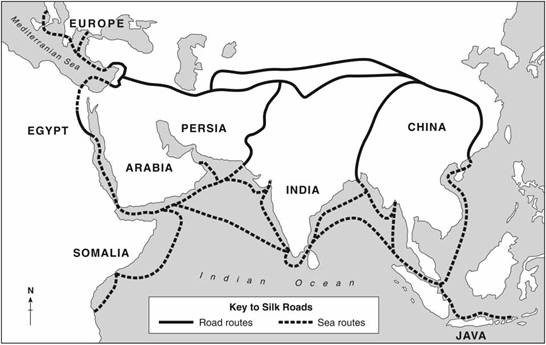

Map 1: The Historic Silk Road

Routes

Source: Shirin Akiner, Silk Roads, Great Games and Central Asia, Asian Affairs, 2011, 42:3, 392.

The Map 1 shows that the Historic Silk Road from China to Rome (Italy)

included both land and sea routes from East to West. In another source, the

Silk Road route from West to East by sea extends from Southern Europe through

Egypt, Arabia, Somalia, Persia, India, Java and then reaches China.[10] Marco Polo, explorer and

tradesman from Italy, also mentioned the Silk Road in his book Il Milione.[11] The outward and inward

routes he and his companions followed were as follows: Outward:

Venice-Acre-Trebizond(Trabzon)-Baghdad-Terbil-Ormuz-Balkh-Kashgar-Lanzhou-(Karakorum)-Lanzhou-Beijing-Chengdu-Pagan;

Inward: Pagan-Chengdu-Beijing-Hangchow-South China Sea-Sumatra-the Indian

Ocean-Arabian Sea-Ormuz-Terbil-Trebizond-Constantinople(İstanbul)-Venice.[12]

As will be seen the Historic Silk Road was actually series of different

routes indicating that it was a combination of multi-modal transportation ways.

However, it should also be noted that the routes are not definite as their

determination presents many difficulties i.e. names of

cities-territories-countries differ from those used in other periods when

attempting to compare them with those available in the various oriental and

occidential sources. For example, Hoço, an ancient Uyghur city in the Turphan

Valley, has been re-named as Kao Chang by the Chinese: this name has never

been used by the Uyghur people.[13]

1.2. Commercial Structure of the Historic Silk Road

Uhlig says that civilisation started with silk. Silk, as one of the first

products to be produced/marketed in a capitalist manner, became not only a

symbol of wealth but also Capital in its own right. Moreover, it was the first

foreign exchange medium between West and East, the first with a convertible

value, and the only commodity equivalent to gold. Furthermore, silk was not

only used to make a fabric; it was the raw material for many other products and

used as a means to promote international relations.[14]

Good ideas and innovations travel far and easily. Historically, they spread

along trade routes. The Historic Silk Road, was, therefore, the vector by which

people, goods, ideas, beliefs, inventions, devices, and techniques were

transmitted. Among the various inventions that travelled its route were paper

(from China), the noria (irrigation waterwheel from Roman Syria), foodstuffs

(apples from Kazakhstan, oranges from China, grapes from the western regions).[15] As an example of a

transmitter of technique, Xueyi et al. studying monetary theory and policy in

China, set out the structure of economic activity in the various dynasties of

ancient China and offer the following details in their paper on monetary

structure for Europe and later North America:[16]

·

Monetary thought was accumulated by thinkers of various vocations in

ancient China.

·

Some monetary theories and concepts in ancient China developed earlier than

in Western countries.

·

Monetary policy was conducted regionally but overseen nationally in

Imperial China.

·

Monetary thought and social development facilitated each other in ancient

China.

·

Ancient monetary thought in China probably travelled along the Silk Road to

Western countries.

While silk is the best known, many other products were traded along the

Silk Road. Caravans moving towards China carried gold and other precious

metals, ivory, precious stones, alfalfa, grapes, sesame, pomegranates, walnuts,

cucumbers, carrots, lions, peacocks, elephants, camels, horses, and glass;

goods which were either unknown or not manufactured in China until the 5th

century A.D. Movements in the opposite direction included furs, ceramics, jade,

bronze objects, lacquer, bambooware, gunpowder, and iron.[17]

Another source lists some of the goods traded in different periods along the

Silk Road as follows: textile products, coral, topaz, wine, glassware, gold and

silver cups, indigo, spices, perfume, rubber, medical lubricants,

tortoise-shell, lapis lazuli, muslin, timber, medicine, pearls, diamonds,

rubies, sapphires, woven silk, and medicinal herbs. Human beings (slaves) were

also traded on these roads.[18]

Information on the organisation and schedule of caravans on the Historic

Silk Road is insufficient, and the frequency of caravans in the different

periods is also unknown. Some documents mention twelve caravans a year in the

1st century A.D. It is, however, uncertain if this number refers to one route

only or to all routes. On the other hand, some documents, state that caravans

were always on the roads, and there was no time when they could not be seen.[19] The Silk Road enriched not

only merchants but also peoples and cultures right across Eurasia.[20] In this context, a stream

of priests and monks also moved Eastward bringing with them the Nestorian,

Manichaean, and Buddhist religions and, later, Islam.[21]

It should be noted that illnesses too were carried on these routes. For

example, the most dreaded of them, the Black Death, or bubonic plague

devastated Europe in the late 1340s after spreading from China.[22]

It is asserted in one source that the heyday of the Historic Silk Road in

terms of transportation density was the 7th and 8th centuries A.D.,[23] while its height in terms

of political security and maintenance of the infrastructure was asserted to be

during the period of Mongol control over the entire transit route in the 13th

and 14th centuries A.D.[24] The latter is confirmed in

another source as The Mongol expansion throughout the Asian continent from

around 1207 to 1360 helped to bring political stability and thus to populate

the Historic Silk Road.[25] However, a further source

states that following the conquest of Baghdad by the Mongols in 1258, transit

trade between East and West from the 13th to the 15th centuries A.D. was

carried out via Egypt, the Red Sea, and the Indian Ocean. Eventual explorations

of sea routes in 16th century caused the weaking of the Historic Silk Road.[26] In this context, sea

transportation with short term direct delivery, replaced long term intermediary

delivery-based journeys. That is, the Historic Silk Road was replaced by ships.[27]

2. The Modern Silk Roads

2.1. Birth of the New Silk Roads

The Silk Road of the past served the numerous traders, armies, and

adventurers as a communication and transport link between cultures and

economies. During the period of the Han Dynasty (B.C.206-A.D.220), the Silk

Road left its mark on the development of civilisations throughout Eurasia by

playing a unique role in foreign trade and political relations as possibly the

worlds first internet linking Asia to Europe and Africa. With the collapse

of the former Soviet Union, a revitalised Historic Silk Road is once again

expected to play an important role in the region's political stability and its

economic development.[28] Exploration for oil and

natural gas reserves being among the main factors for the renaissance of these

roads.

Three memorable metaphors about the region date from the 19th century:[29]

1.

The first is The Historic Silk Road coined by Ferdinand von Richthofen in

1877. This encapsulates the sense of mystery and exotic splendour of the

ancient trade routes. Today, the current term the New Silk Roads is used as a

metaphor for reconnection. It implies transport corridors, international trade,

oil and gas pipelines, and tourism.

2.

The second 19th century metaphor the Great Game, is thought to have been

invented by Arthur Conolly around 1840. It too evokes all the intrigue, daring,

and heroism of the Russo-British struggle for supremacy in the land north of

the Hindu Kush. Todays New Great Game is taking place as the great powers

continue their pursuit of rival political and economic goals. The main players

now being Russia, China, and the United States - the US taking the place of

Britain with Turkey, Iran, Pakistan, and India playing secondary roles. The

EU and Japan are also involved.

3.

Finally, Central Asia, the notional locus for the Historic Silk Road and

the Great Game is, in fact, a mythical area being no more than a term invented

in 1843 by the famous geographer and explorer, Alexander von Humboldt, to refer

to this fuzzy region, somewhere between Europe and Asia.

The opening-up of Central Asia and the Caucasus has revived the use of two

of the above-mentioned historical metaphors -The Historic Silk Road and The

Great Game- to characterize the economic and political transition in these

regions. Currently, however, neither is applicable in their historical sense.

Moreover, the inherent contradiction in these ideas (that is, the Historic Silk

Road meaning international free trade, and the Great Game implying national

power and trade controls) may serve to mask some of the more interesting political

and economic realignments taking place as leaders in the Caucasus and Central

Asia seek to diversify their foreign policy options.[30]

It should, however, be noted that the new self confident and assertive Central

Asian states set the rules. So that whereas in the 19th century the great

powers set the agenda, it is now principally the Central Asian states that take

the decisions on the establishment of partnerships, doing business, and

permitting access to their resources.[31]

In terms of significant economic and political aspects, Central Asia is

important for India as it too searches for New Silk Roads. However, the best

short routes from India to Central Asia pass through Pakistan, Afghanistan or

China, and Indias relationship with these countries is tense due to past

battles. India, therefore, now avoids problems with China and Pakistan in order

to normalise their commercial relations[32]

and thereby benefit from the advantages of the Region. Central Asian economies

also attract South Asian countries. For instance, after Uzbekistan gained its

independence in 1991 South Asian entrepreneurs from Pakistan and Afghanistan as

well as India flocked to it and to other Central Asian economies, bringing

capital, information, and technology.[33]

In recent years, some efforts have been made to develop East Asias

economic potential. For example, South Korea wants to specialize in certain key

strategic industries while becoming the region's business hub. Russia wants to

exploit the vast eastern region for its natural resources and build a railway

connecting Europe to East Asia. Japan wants to end its economic crisis, while

China seeks to bring about a new era of prosperity for its people. However,

these aspirations are subject to change because of North Koreas stated intention

to develop nuclear weapons. In the light of this, regional nations are obliged

to balance their economic priorities with issues of political and military

security.[34]

Japan, however, is initiating various strategies. In this context, in July

of 1997 its former Prime Minister Ryutaro Hashimoto announced the start of

Japans new Eurasian Diplomacy. Recognising the fact that the Silk Road also

runs east he stated his conviction that it was time to develop a Pacific

perspective, to envision through Asian eyes a region encompassing Russia,

China, the states of Central Asia and the Caucasus. Oil and gas, while

important, are not the sole reasons for Japan to become involved. As an Asian

country it could serve as a non-Western example of successful modernisation and

forward-looking industrial policy.[35]

2.2. International Initiatives and the New Silk Roads

Regarded as being the godfather of geopolitics Halford Mackinder argued

more than a century ago that, whoever controls the Eurasian world island

would control the world. For this purpose, there are various initiatives,

already launched or yet to be started, under the umbrella title of the New Silk

Roads. Among these the Historic Silk Road takes its place at the core of

relevant projects. Economic and political aspects are certainly among the aims

of such initiatives, but it is also felt that the New Silk Roads could promote

security, prosperity, and connectivity within some of the most volatile,

impoverished, and isolated nations on the planet.[36]

Akiner states that the New Silk Roads are symbolised as being based on mutual

interest, peace, and stability and that it is a revitalisation of the Historic

Silk Road.[37]

The concept the Modern Silk Roads or the New Silk Roads contains several

meanings depending upon the views/aims/projections of the countries and/or

country groups on the region. Major among such initiatives are the Transport

Corridor Europe Caucasus Asia (TRACECA), the Northern Distribution Network

(NSR-NDN), the Trans-Korean Railroad with the Trans-Siberian Railroad (TKR-TSR;

Iron Silk Road), and the Gulf-Asia Model. Brief information about these

initiatives is given below and their connection with the Historic Silk Road

revealed. As will be seen, the main factors for the establishment of the said

initiatives are oil and natural gas plus some others.

China and the Central Asian countries were among the main actors on the

Historic Silk Road. In this context, trade between these countries has always been

crucial and favoured by both sides. However, earlier relationships have faced

changes. Items such as jade, tea, silk, and rhubarb have been replaced by crude

oil, natural gas, weapons, and infrastructure. The Historic Silk Road is

regarded as having been revived in terms of new trade in energy. Central Asian

states have huge hydrocarbon potential which have not yet been fully explored

and they seek foreign participation in developing and transporting these

reserves. Russia, the Western countries and China are the influential partners

for the Central Asian states in terms of moving their hydrocarbon resources

and, accordingly there is a major struggle for dominance among these actors.

For example, following the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991, China speedily

established diplomatic relations and signed a series of agreements on bilateral

economic cooperation with Central Asian states.[38]

One of the European Unions (EU) projects designed to assist the former

Soviet Union countries with regard to the development of trade in Eurasia, is

the so-called renaissance of the Historic Silk Road, TRACECA. The concept was

first developed during an EU meeting held in Brussels in 1993 with the

declaration of the revitalisation of the ancient

Russia, has reacted to these developments. An announcement from Moscow in

July 1999 stated that it intended to levy duties on oil exported to non-Customs

Union CIS countries -this includes those countries most heavily involved in the

TRACECA programmes- to prevent Russian oil from being resold to Western Europe

at cheaper prices through alternative routes. Russian tax revenue losses may

well be real, however, Moscows actual message is more political than economic.

If the states around the Caspian Basin choose to enter into economic relations

against the interests of their more powerful neighbours, they are certainly at

risk in doing so. However, the situation in Central Asia and the Caucasus is

now very different from the 19th century when Russia and Britain competed for

influence among separate tribes in the original Great Game; these newly

independent states are no longer passive pawns in the process.[43]

The US, Russia, and China all have their own Central Asia integration

schemes in the security and economic spheres: China has the Shanghai

Cooperation Organization (SCO), Russia the Collective Security Treaty

Organization (CSTO), and the US the New Silk Road (NSR).[44]

The NSR strategy, declared by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and senior US

officials in the first half of 2009 is a key aspect of the US plan to promote

stability in Central Asia following the departure of 33,000 American and NATO

troops from Afghanistan by 2014. As Clinton sees it, commodity and energy

exports have the ability to reveal the potential of regional economies. The

proposed NSR projects includes establishment of the following transit

corridors: completing the Afghanistans Ring Road; linking railways between

Afghanistan and Pakistan; constructing the

Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) pipeline; implementing the

Central Asia Counternarcotics Initiative (CACI); and forming a regional

electricity market by building a transmission line between Central Asia and

South Asia (CASA-1000).[45]

These new supply lines have been termed the Northern Distribution Network

(NDN) which underscores a demilitarized, commercial nature as well as an

open-ended vision of a multiplicity of supply routes to Afghanistan.[46] The central element of the

NSR is to develop and expand the NDN which aims to transport large quantities

of non-lethal supplies from Europe to the NATO troops in Afghanistan through

Russia, the Caucasus, and Central Asia.[47]

The NDN Routes are as follows: Pakistan Route: Pakistan-Afghanistan; North

Route: Latvia-Russia-Kazakhstan-Uzbekistan-Afghanistan; South Route:

Georgia-Azerbaijan-Kazakhstan-Uzbekistan-Afghanistan; KKT Route:

Kazakhstan-Kyrgyzstan-Tajikistan-Afghanistan. While the creation of the NDN was

motivated by the U.S. militarys immediate logistical needs, its establishment

offers a unique opportunity for Washington to establish a New Silk Road, which

would help stabilize Afghanistan in the long term, and transform Eurasia too.[48]

The TKR-TSR, another extension of the New Silk Roads established between

Korea and Russia with the involvement of several other countries, has

implications for the North's domestic economy, inter-Korean relations, both the

Koreas' wider foreign relations and Russia's Asian policy. This linkage is also

of great importance to other major powers: China, Japan, and the U.S., all of

which have vital interests in the peaceful resolution of the division of Korea.

The other larger implications that emerge from consideration of the TSR-TKR and

from other similar programmes to develop Asia are as follows:[49]

·

All projects for Korean and trans-national regions of Asia's economic

development must overcome strong domestic opposition to succeed.

·

This programme shares a common denominator with other projects such as the

joint Russo-Iranian-Indian project and the TRACECA for developing Asian

infrastructure.

·

This programme is, implicitly or even explicitly, an effort to limit

China's political-economic power over Asia, especially the Korean peninsula and

Russia's Far East.

·

This programme and other tied projects represent individual parts of a much

larger process that aims to overcome major obstacles to development, security,

prosperity, and stability in Asia.

The GulfAsia model, another initiative between the Gulf and Asian

countries, has a simple target: the Gulf exports energy and energy-related

products, and imports Asian manufactured goods, construction services, food,

and labour. The fact that oil and gas is considered to be a strategic sector by

governments of both regions limits investment opportunities. Nevertheless, some

significant direct investments have been made. For example, national oil

companies (NOCs) in the Gulf have positioned themselves as strategic investment

partners with Asian customers.[50] In this context, for

example, the Gulf region is likely to meet Chinas growing need for natural

gas. Iran, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates are, after Russia,

the second, third, fourth, and fifth natural gas holders of the world. Gulf

Region governments have also been opening their doors to foreign investment in

natural gas operations.[51]

An example of partnership in this model is as follows: Asian firms showed

great interest in Iraq after the country opened up its oil industry to foreign

companies in 2008, and they won several licences. China's main state oil

companies; China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), China National Offshore

Oil Corporation (CNOOC), and China Petroleum & Chemical Corporation

(SINOPEC; operating in Kurdistan) have secured strong footholds in the country,

alongside Western international oil companies. The financial markets of

Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and Viet Nam attract Gulf investors and have

relatively better foreign investment possibilities as they also offer

investment opportunities in the sectors in which Gulf investors are

experienced: real estate, energy, tourism, and banking. The Gulf States could

also be a hub for transhipment, re-export, and service provision, as shown by

Dubai's entrepot model which has made the UAE India's largest trading partner

since 2008.[52]

2.3. Commercial Potential of the New Silk Roads

Central Asia and the Caspian basin take centre place

in the New Silk Roads. The region is split between oil and gas-rich states such

as Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan (Group A) and states

such as Armenia, Georgia, Tajikistan, and Kyrgystan (Group B) which lack

meaningful petroleum resources. The countries in Group A, rather than simply

being a transit corridor, expect to exploit their oil and natural gas reserves

as the means to revitalise their overall economies, while the countries in

Group B, facing different economic choices, hope to take advantage of their

geographic position to encourage the development of transportation

infrastructure, thus allowing them to share in the good fortune of their

neighbours oil and gas resources.[53]

Structural changes in the world economy have accelerated the economic

realignment of the two regions. China's economy grew fifteen-fold between 1980

and 2011 to become the world's second-largest after the US. By 2050, India is

expected to be the world's third-largest economy. On current trends, Asia could

account for half of global output by then. Even now Asia accounts for 50% of

Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) trade, a big change from 30 years ago when some

80% of GCC trade was with the developed economies of Europe and the US.[54]

Given its geographic location and oil-producing capacity, the Middle East

will probably remain as the main supplier of energy to Asia. Imports already

meet 75% of Asian demand, and are expected to account for 90% by 2030. The

Middle East already supplies about 60% of China's oil needs.[55] There are various reasons

for this rise in Chinas energy consumption, the first of which is its rapid

economic growth. While its share in the primary energy demand on a world scale

was 5% in 1971, by 1995 it had increased to 11%. In 1993 Chinas crude oil

consumption was already more than its domestic production. Since then, its

import volume has increased and if this trend in economic activity continues,

Chinas demand for oil could be as high as 7-12 million barrels per day (mbl/d)

by 2020.[56]

All Central Asian states come within the middle-income range of countries.

Information on these are as follows:[57]

·

Kazakhstan is the richest with its GDP. This is mainly because of its very

large territory and world-class reserves of oil, gas, uranium, and lithium. It

also has grain, cattle and other resources. According to one source, Kazakhstan

has oil reserves of 8.0 billion barrels (bbl) and 65.0 trillion cubic feet of

natural gas. Another source states that it has 5.4 bbl of crude oil reserves.[58] By 1998, oil accounted for

more than 60% of its exports.[59]

·

Turkmenistan, too, has huge gas reserves and is a major producer of cotton.

One source gives Turkmenistan oil reserves of 0.5 bbl and 101.0 trillion cubic

feet of natural gas.[60] According to the 2012

Statistical Review, it holds 11.7 percent of the worlds proven natural gas

reserves.[61] Oil and gas constitute 80%

of its revenue.[62]

·

Uzbekistan is a balanced economy with many different resources including

very large reserves of gold. It is also one of the top cotton producers of the

world; Bukhara, for instance, exported over a million tonnes of cotton in 1998,

150,000 of which were exported via TRACECA.[63]

·

The two mountain states of Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan both have some gold

and hydropower reserves. However, these are the poorest states.

Information on some of the countries in the Caucasian and Caspian regions

are as follows:

·

Armenia has a small-scale agricultural economic structure. According to the

2012 statistics, its GDP composition by sector of origin is as follows:

agriculture: 21.1%, industry: 37.7%, services: 41.2%. The country has no proven

crude oil and natural gas reserves as of 2012.[64]

·

Azerbaijan is relatively an industrial country. According to the 2012

statistics, its GDP composition by sector of origin is as follows: agriculture:

6%, industry: 63.8%, services: 30.2%. The country has 7 bbl proven crude oil

reserves and 849.5 billion cubic metres (bcm) of natural gas reserves as

of 2012.[65]

·

Georgia is relatively a service based economy and its GDP composition by

sector of origin is as follows according to the 2012 statistics: agriculture:

7.8%, industry: 23%, services: 69.2%. It has 33.19 million barrels (mbl) proven

crude oil reserves and 93.41 bcm of natural gas reserves as of 2012.[66]

All initiatives are candidates designed to increase the commercial

potential of the countries related to the New Silk Roads. For example, the

NSR-NDN could generate huge economic advantages among both trading and transit

states. Some of these are as follows: [67]

Firstly, an overland route running from Lianyungang to Rotterdam via Xinjiang

and Central Asia would reduce the time it takes to transport goods from China

to Europe from 20-40 days to about 11 and lower costs from $167 to $111 per

ton, i.e. by over 30% while cutting the present journey time by half. Secondly,

a UN study has estimated that GDP across Central Asia would grow by 50% within

a decade if the related states cooperate with each other on fostering trade.

Thirdly, intercontinental trade is projected to increase Afghanistans GDP by

8.8-12.7% and 2-3% in Xinjiang.

3. The Silk Roads and Turkey

3.1. The Role of Turkey in the Historic Silk Road

The main route of the Historic Silk Road linking China with the Byzantine

Empire was, to a large extent, under the control of the Turks. Starting from

the north of Beijing the boundaries of the Turkic territories passed through

Iran, Khorasan, the Ural Mountains, and Caspian Sea to reach the Black Sea.

They neighboured the major states of those times; China, Iran, and the

Byzantine Empire. Thus the Historic Silk Road played an important role for

Turks in the establishment and improvement of their economic relations with

China, the Caucasus, Russia, India, and the Arab countries. The Turks played a

paramount role in making the Historic Silk Road famous and this is clearly

recognized in an Uzbek saying: There are two big roads in the universe; the

Milky Way in the sky and the Silk Road on earth.[68]

Turks also took part in relevant production and trade processes. For

instance, in the 6th A.D., Turks not only manufactured and sold very popular

gilded armour but also horseshoes, horse riding equipment, and farmers hand

tools. In this way they developed their economy, becoming the main exporter in

China to the West. Moreover, Iran was the fashion centre for Chinese elegance

in those times, as Paris was for Europe a hundred years ago. Turks were the

greatest beneficiaries of this situation as they were traders in silk from both

Iran and the Byzantine lands. That is, they were selling the silk of Iran and

the Byzantine lands to China which had once been the biggest exporter of this

commodity.[69]

Prior to the exploration of new seaways in the 17th century, India in the

Historic Silk Roads eastern region had been one of the most important trading

centres. As a consequence it was regularly attacked by dynasties of Turks from

Central Asia and Afghanistan. India was ruled by Turkic dynasties from the 13th

to the 19th centuries. The most influential of these was the Mughal (Mongol)

Empire which ruled from 1526 to 1857. Turkic dynasties encouraged Turks to

spread from Central Asia so that a commercial network, mainly under the

management of Turkic administrators was established along the Historic Silk

Road from India to Anatolia in todays Turkey.[70]

Current boundaries of Turkey have had connections with the Silk Road routes

throughout history. In this context;

·

During the time of the Asian Hun State between the 2nd century BC and the 4th

century A.D., the route from West to East included Antioch (Antakya), a

Rоman city then in Syria.[71]

·

In the 9th century A.D. the main commercial centres of the Parthian Empire

in the East and the Rome-Parthia frontier were Zeugma (Belkıs) on the bank of the

Euphrates and Antiocheia (Antakya) on the bank of the Orontes river (Asi).[72]

·

The outward and inward routes of Marco Polo and his companions included

cities of modern Turkey: Outward:

Venice-Acre-Trebizond(Trabzon)-Baghdad-Terbil-Ormuz-Balkh-Kashgar-Lanzhou-(Karakorum)-Lanzhou-Beijing-Chengdu-Pagan;

Inward: Pagan-Chengdu-Beijing-Hangchow-South China Sea-Sumatra-the Indian

Ocean-Arabian Sea-Ormuz-Terbil-Trebizond-Constantinople(İstanbul)-Venice.[73]

·

According to another source, many cities in Turkey were included in the

routes. Among them are; South to East: the Mesopotamia Region-Antakya and

Gaziantep (Anatolia)-the Iran-Pamir Plain; South to West: Gaziantep and Malatya

(Anatolia)-Thrace (Trakya)-İzmir (Aegea); North to West: Trabzon and Sinop

(Black Sea)-Alanya and Antalya (Mediterranean)-Europe.[74]

·

İzmir was the western end point of Asia and among the last cities on the

Historic Silk Road.[75] The Ottoman-Iran Wars between 1588-1628 adversely affected the

economy of the Armenians dealing with the silk trade and, as a consequence,

they re-directed their business from Aleppo to İzmir Harbour. Thus the Historic

Silk Road extending from East to West was; Iran Kashan, Kum, Tehran, Qazvin,

Tabriz, Yerevan, Kars, Erzurum, Tokat, Ankara, Afyon, Denizli (Laodicea),

Nazilli (Mastaura), Sultanhisar (Nysa), Aydın (Tralleis), Menderes Magnesias,

Selçuk (Ephesus), and İzmir. In this way İzmir regained its importance in the

business of the transportation of goods.[76]

At different periods, Turks took many measures to continue their connection

with the Silk Road. Some of which are given below:[77]

·

The Seljuks constructed good, soundly built, roads to ensure the safety of

transportation activities in Anatolia.[78]

·

The Ottoman Empire allowed commercial activities coming from Aleppo via the

Historic Silk Road, to flow directly to İzmir.

·

The aim of the Ottoman tax concessions that began in the 16th century under

the Capitulations was to redirect commercial activities to Anatolia and the

Silk Road. At that time many traders from the Netherlands, Britain, and the

Levantine came to the Ottoman Empire.

·

After the fall of Andalusia, the Ottoman Empire took some displaced Jews

under its protection. There were two reasons for such a decision, the first of

which was humanitarian and the second economic. In this context, the Ottoman

Empire, wishing to benefit from the Jewish banking experience, settled them in

the major trading cities of İzmir, Thessaloniki, and İstanbul in order that the

commercial flow be redirected away from South Africa and towards Anatolia and

inner Asia, that is, to the Silk Road.

However, due to the decline in the significance of the Historic Silk Road,

the following events concerning the Anatolian connection occured:[79]

·

As the Ottoman Empire weakened the Anatolian route lost its importance in

terms of being the commercial and cultural bridge between East and West.

·

At the end of the Ottoman period, the burgeoning railway system saw a

dramatic decline in traditional transport routes.

Currently, the Historic Silk Road is being revitalised in terms of its

touristic potential in addition to international initiatives aimed at meeting

economic and political targets. In this context, Turkey, in addition to its

involvement in the foregoing commercial activities, is undertaking various

restoration/renovation activities. For this purpose, 11 caravanserais on the

Anatolian routes have been restored by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism and

made ready for visitors. These are:[80]

Ağzıkara (Aksaray), Ak (Denizli), Alara (Antalya), Alay (Aksaray), Çardak

(Denizli), İncir (Burdur), Sarı (Nevşehir), Silahtar Mustafa Paşa (Malatya),

Sultan (Aksaray), Susuz (Burdur), Şarapsa (Antalya).

3.2. The Role of Turkey in the New Silk Roads

Due to its geo-strategic position, Turkey, in terms of its political and

economic aspects, is involved in most of the international initiatives relating

to the New Silk Roads. Here, I offer some information concerning its role and

the impact of the initiatives on the country. Turkey is involved in the

so-called Asian Silk Road (oil and gas pipeline projects), the European Silk

Road (TRACECA), and the American Silk Road (NSR-NDN). It is not involved in the

so-called Korean-Russian Silk Road (TKR-TSR) and the Gulfian Silk Road (the

Gulf-Asia Model) due to its distance from such initiatives.

The long-term stability of the Caucasian and Central Asian states will

depend on their ability to attract foreign direct investment to build their economies,

while at the same time restoring their traditional cultural and commercial

relations with Russia, Iran, and Turkey. Potential markets in Turkey and

Europe, however, already rely on Russian natural gas imports which are likely

to remain as a cheaper alternative to Caucasian or Central Asian gas for some

time. Turkmenistan has explored a variety of options to export gas to Turkeys

markets through either Iran or via a cross-Caspian pipeline, but the capital

costs for the development of these routes make its gas more expensive.

Nevertheless, for strategic reasons Turkey decided on using Turkmen gas to

diversify its energy sources. For now, though, Russian or Azeri options remain

as the commercial routes of choice.[81]

In this context, Turkey is

actively involved in the international oil and natural gas pipeline projects.

As of 2013, the international crude oil pipeline projects (COPP) in line with

the Historic Silk Road routes are as follows: Iraq-Turkey (Kerkuk-Ceyhan) COPP

(two pipelines) and the Azerbaijan-Georgia-Turkey (Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan) COPP.

In addition to these the international natural gas pipeline projects (NGPP)

that Turkey is involved in through its state company BOTAŞ as of 2013 are as

follows: Turkey-Greece-Italy NGPP (ITGI); Turkey-Bulgaria-Romania-Hungary-Austria

NGPP (NABUCCO); Trans-Anatolian NGPP (TANAP); Iraq-Turkey NGPP; and

Trans-Caspian Turkmenistan-Turkey-Europe NGPP.[82]

TRACECA is important for Turkey. Starting in Eastern Europe (Bulgaria,

Romania, Ukraine) the corridor passes through Turkey, crossing the Black Sea to

the ports of Poti and Batumi in Georgia. It then uses the transport network of

the Southern Caucasus. From Azerbaijan it crosses the Caspian Sea

(Baku-Turkmenbashi, Baku-Aktau) and meets the railway networks of the Central

Asian states of Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan whose transport networks are

connected to Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and eventually to China and

Afghanistan.[83] There are, however, some

barriers to the execution of the TRACECA. The conflicts between Turkey and

Armenia, Armenia and Azerbaijan, Georgia and Russia, and between Iran and the

USA, plus disputes over the the Caspian Sea oil fields, are major obstacles to

the realization of the project. In addition to these, regional instabilities in

Abkhazia and Southern Ossetia and in Nagorno (Mountainous) Karabakh, may cause

problems for the implementation of the Project. Furthermore, as the TRACECA

will be an alternative to the Moscow-centred trade and transport flows reaching

Europe, Russia is actively lobbying for alternative roads via its own

territory. In addition to this, as the TRACECA roads are opened up, the

northern countries will inevitably place increasing emphasis on improving

services in order to maintain the competitive advantage of their transport

corridors.[84]

Within the framework of the NSR-NDN, and with the planned US and NATO

withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2014, the major powers are all competing to

increase their influence in Central Asia. Other states: India, Pakistan, Iran,

Turkey, and the EU have also involved themselves in this rivalry.[85] In this context, for

instance, Turkey is also involved in the network which comprises a rail link

starting in Latvia and passing through Russia, Kazakhstan, and Uzbekistan; a

road route via Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan for goods initially delivered to the

Manas Transit Centre near Bishkek (Kyrgyzstan); and a Caucasus pathway that

ferries cargo from the US and Europe to the port of Mersin (Turkey), and to

Poti (Georgia), for delivery via the Caspian Sea to Afghanistan.[86]

While giving particular importance to the revitalisation of the Historic

Silk Road by restoring its heritage sites, Turkey, as mentioned above, also

seeks to increase its role in the New Silk Roads. In this context, Ahmet

Davutoğlu, Turkeys Minister of Foreign Affairs, emphasized the projections

concerning the revitalisation of the Historic Silk Road and the importance of

taking part in the plans for the New Silk Roads.[87]

A senior official in the same Ministry also emphasized the significance of the

Historic-New Silk Roads and proposed various measures for their revitalisation.

In this context, while he placed emphasis on the missing section between

İstanbul and Beijing in the İstanbul-Europe-USA-China link in the context of

the Historic Silk Road, he recommended the following:[88]

·

The nations between China and Turkey have not yet been integrated into the

global economy. The most significant element in this chain is the need for

economic reconciliation between Turkey and Iran.

·

A strategic collaboration between Turkey, Iran, and Russia is a must for

the revitalisation of the Historic Silk Road.

·

As this would result in vital benefits for the West they should commit

themselves to fashioning this missing link.

3.3. The Impact of the New Silk Roads on Turkeys Foreign Trade

As mentioned earlier, the New Silk Roads are on the revitalised Historic

Silk Road routes and their peripheral areas. The countries/territories of

todays world involved in the Historic Silk Road -inclusive of its secondary

connections- are as follows:[89] Land Routes: China,

Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Pakistan,

Afghanistan, Bhutan, Nepal, India, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Russia, Azerbaijan,

Georgia, Armenia, and Turkey; Sea Routes: China, Viet Nam, Cambodia, Malaysia,

Indonesia, East Timor, Myanmar, Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Oman,

Yemen, Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania, Djibouti, Eritrea, Sudan, Egypt, Lebanon,

Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Syria, Turkey, Bulgaria, Greece, and Italy. There

are 19 countries/territories on the land routes and 29 on the sea routes.

Excluding the repetitions in both routes, there are, as of today, some 43

countries/territories along the Historic Silk Road. This indicates a clear

connection between the Historic and the New Silk Roads.

Below, the impacts of the New Silk Roads on Turkeys foreign trade are

given. For this purpose, the countries having direct relations with Turkey are

taken into account in terms of collaboration in the oil and gas projects, and

relevant assessments are made. In this context, details

concerning the international COPP of Turkey are available in Table 1.

Table 1: International COPP of Turkey (2013)

|

|

Lenght (km) |

Capacity [million barrels per annum (mbla)] |

||

|

Iraq-Turkey COPP (Kerkuk-Ceyhan) |

|

Turkey |

Total |

553 |

|

Line I |

641 |

986 |

||

|

Line II |

656 |

890 |

||

|

Grand Total |

1,297 |

1,876 |

||

|

Azerbaijan-Georgia-Turkey COPP (Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan) |

|

Turkey |

Total |

365 |

|

|

1,076 |

1,776 |

||

Source: BOTAŞ, Annual Report,

2011, Ankara, 29.

Currently, Turkey has two international COPPs, one of which is with Iraq,

the other with Azerbaijan and Georgia. While the first has two lines with a

total length of

Table 2: Crude Oil Transportation through Iraq-Turkey COPP (2002-11) [000 barrels (bl)]

|

Year |

2002 |

2003 |

2004 |

2005 |

2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

|

Amount |

175,667 |

60,278 |

37,685 |

13,167 |

12,932 |

43,700 |

132,941 |

167,467 |

144,590 |

163,276 |

Source: BOTAŞ, Annual Report,

2011, Ankara, 29.

According to the crude oil statistics of BOTAŞ, there was a decline in transportation

between 2002-07 due mainly to unrest in Iraq. From 2007 on, the trend was

upward, and for 2011 the amount moved was 163,276,000 bl.

Details of the international

natural gas pipeline projects (NGPP) in which Turkey is involved as of 2013 are

as follows: [90]

·

Turkey-Greece-Italy NGPP (ITGI):

3.6 bcma (billion cubic metres per annum) of gas to Greece and 8.0 bcma of gas

to Italy, a total of 11.6 bcma of gas will be transported to Europe from the

Caspian Region via Turkey.

·

Turkey-Bulgaria-Romania-Hungary-Austria

NGPP (NABUCCO): The gas produced in Azerbaijan (Shah Deniz), Iraq,

Turkmenistan, and other Caspian sources, plus Egypt and Iran, is planned to be

the source for the line, the transportation capacity of which will be 31 bcma.

The total length of the pipeline is

·

Trans-Anatolian NGPP (TANAP): In

agreement with SOCAR (Azerbaijan), 10 bcma of Shah Deniz Phase-II gas will be

transported via the BOTAŞ natural

gas transmission system from the borders of Greece and Bulgaria to Europe.

·

Iraq-Turkey NGPP: This is an

integrated project, involving field development, production, gas processing,

and pipeline construction for natural gas reserves in Northern Iraq intended to

develop a natural gas corridor between Iraq and Turkey by transporting 10-12

bcma gas to Turkey and Europe.

·

Trans-Caspian

Turkmenistan-Turkey-Europe NGPP: Natural gas produced in southern Turkmenistan

will be transported by pipeline via the Caspian Sea to Turkey and then to

Europe. 30 bcma of Turkmen gas will be transported through this pipeline, 16

bcma of which is to be supplied to Turkey, and 14 bcma to Europe.

In the context of the New Silk Roads in line with the Historic Silk Road routes,

the projects in which Turkey has roles include the following countries, which

means that they are foreign trade partners whose trade volume is given in Table

3:

·

COPP: Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iraq

·

NGPP: Austria, Azerbaijan,

Bulgaria, Greece, Hungary, Iraq, Italy, Romania, Turkmenistan

·

TRACECA: Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Georgia, Iran, Kazakhstan,

Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Romania, Tajikistan, Ukraine, Uzbekistan

·

NSR-NDN: Afghanistan, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Pakistan,

Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan

Turkeys involvement in all these projects is expected to result in an

increase in volume of its foreign trade. Thus, such New Silk Roads are

increasing Turkeys trade capacity as the Historic Silk Road did in the past.

Table 3: Foreign Trade of

Turkey with the COPP Countries (1996-2012) (000 $)

|

Countries |

|

1996 |

2000 |

2005 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

|

Azerbaijan |

E (*) |

239,903 |

230,375 |

528,076 |

1,550,479 |

2,063,966 |

2,584,671 |

|

I (**) |

39,165 |

95,615 |

208,325 |

252,525 |

262,263 |

339,936 |

|

|

Georgia |

E |

110,319 |

131,771 |

271,828 |

769,271 |

1,092,321 |

1,253,309 |

|

I |

32,495 |

155,315 |

289,834 |

290,725 |

314,352 |

180,351 |

|

|

Iraq |

E |

--- |

--- |

2,750,080 |

6,036,362 |

8,310,130 |

10,822,144 |

|

I |

--- |

31,788 |

66,434 |

153,476 |

86,753 |

149,328 |

* Export, ** Import

Source: TÜİK, Main Statistics; Foreign Trade, http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/UstMenu.do?metod=temelist, Retrieval date: 30.08.2013.

Between 1996 and 2012 Turkey increased both its export and import volume

with Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Iraq. Crude oil had a paramount effect in this

upward trend. The trade volume with Iraq is particularly noteworthy from 2010

onwards. (pls. see Table 3)

Table 4: Foreign Trade of

Turkey with the NGPP Countries (1996-2012) (000

$)

|

Countries |

|

1996 |

2000 |

2005 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

|

Austria |

E |

290,514 |

292,930 |

659,097 |

835,181 |

1,052,932 |

1,000,745 |

|

I |

545,485 |

516,754 |

940,056 |

1,439,448 |

1,736,366 |

1,634,272 |

|

|

Azerbaijan |

E |

239,903 |

230,375 |

528,076 |

1,550,479 |

2,063,966 |

2,584,671 |

|

I |

39,165 |

95,615 |

208,325 |

252,525 |

262,263 |

339,936 |

|

|

E |

156,906 |

252,934 |

1,179,313 |

1,497,384 |

1,622,777 |

1,684,989 |

|

|

I |

362,771 |

465,408 |

1,190,079 |

1,702,534 |

2,474,621 |

2,753,650 |

|

|

Greece |

E |

236,464 |

437,725 |

1,126,678 |

1,455,678 |

1,553,312 |

1,401,401 |

|

I |

284,959 |

430,813 |

727,830 |

1,541,600 |

2,568,826 |

3,539,869 |

|

|

Hungary |

E |

102,808 |

109,994 |

379,092 |

440,766 |

508,648 |

517,874 |

|

I |

94,420 |

216,262 |

946,238 |

1,382,213 |

1,494,488 |

1,184,452 |

|

|

Iraq |

E |

--- |

--- |

2,750,080 |

6,036,362 |

8,310,130 |

10,822,144 |

|

I |

--- |

31,788 |

66,434 |

153,476 |

86,753 |

149,328 |

|

|

Italy |

E |

1,446,419 |

1,789,307 |

5,616,755 |

6,505,277 |

7,851,480 |

6,373,080 |

|

I |

4,285,793 |

4,332,788 |

7,566,262 |

10,139,888 |

13,449,861 |

13,344,468 |

|

|

Romania |

E |

314,045 |

325,818 |

1,785,409 |

2,599,380 |

2,878,760 |

2,495,427 |

|

I |

441,290 |

673,928 |

2,285,592 |

3,449,195 |

3,801,297 |

3,236,425 |

|

|

Turkmenistan |

E |

65,657 |

120,155 |

180,635 |

1,139,825 |

1,493,336 |

1,480,052 |

|

I |

100,314 |

97,878 |

160,744 |

386,342 |

392,712 |

303,507 |

Source: TÜİK, ibid.

The volume of Turkeys foreign trade with countries involved in the NGPP

has also increased. However, except for Azerbaijan and Iraq, partners in COPP, plus

Turkmenistan, all countries in this group export more than Turkey. That is,

Turkey has a trade deficit with these countries (pls. see Table 4). This

demonstrates that such projects are also aimed at removing the trade gap

between Turkey and these countries. Turkey is expected to raise its export

volume above its import volume with the countries in the NGPP via bilateral

trade agreements.

Table 5: Foreign Trade of

Turkey with the TRACECA Countries (1996-2012) (000 $)

|

Countries |

|

1996 |

2000 |

2005 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

|

Armenia |

E |

--- |

--- |

--- |

16 |

218 |

241 |

|

I |

--- |

--- |

392 |

2,626 |

133 |

222 |

|

|

Azerbaijan |

E |

239,903 |

230,375 |

528,076 |

1,550,479 |

2,063,966 |

2,584,671 |

|

I |

39,165 |

95,615 |

208,325 |

252,525 |

262,263 |

339,936 |

|

|

Bulgaria |

E |

156,906 |

252,934 |

1,179,313 |

1,497,384 |

1,622,777 |

1,684,989 |

|

I |

362,771 |

465,408 |

1,190,079 |

1,702,534 |

2,474,621 |

2,753,650 |

|

|

Georgia |

E |

110,319 |

131,771 |

271,828 |

769,271 |

1,092,321 |

1,253,309 |

|

I |

32,495 |

155,315 |

289,834 |

290,725 |

314,352 |

180,351 |

|

|

Iran |

E |

--- |

297,521 |

235,785 |

912,940 |

3,589,635 |

3,044,177 |

|

I |

--- |

--- |

806,335 |

815,730 |

12,461,532 |

3,469,706 |

|

|

Kazakhstan |

E |

164,044 |

118,701 |

459,946 |

818,900 |

947,822 |

1,068,625 |

|

I |

100,595 |

346,376 |

558,900 |

1,392,528 |

1,995,115 |

2,056,086 |

|

|

Kyrgyzstan |

E |

47,100 |

20,572 |

89,529 |

129,902 |

180,241 |

257,470 |

|

I |

5,879 |

2,350 |

14,113 |

30,900 |

52,123 |

45,226 |

|

|

Moldova |

E |

14,397 |

26,232 |

81,108 |

148,209 |

208,885 |

224,464 |

|

I |

14,468 |

7,047 |

31,447 |

110,732 |

244,482 |

135,053 |

|

|

Romania |

E |

314,045 |

325,818 |

1,785,409 |

2,599,380 |

2,878,760 |

2,495,427 |

|

I |

441,290 |

673,928 |

2,285,592 |

3,449,195 |

3,801,297 |

3,236,425 |

|

|

Tajikistan |

E |

4,444 |

4,467 |

46,717 |

143,890 |

172,575 |

234,947 |

|

I |

2,786 |

16,511 |

47,309 |

283,689 |

324,283 |

345,178 |

|

|

Ukraine |

E |

267,539 |

258,121 |

821,034 |

1,260,423 |

1,729,760 |

1,829,207 |

|

I |

761,658 |

981,560 |

2,651,017 |

3,832,744 |

4,812,060 |

4,394,200 |

|

|

Uzbekistan |

E |

230,492 |

82,647 |

151,071 |

282,666 |

354,490 |

449,884 |

|

I |

58,054 |

85,794 |

261,466 |

861,373 |

939,882 |

813,287 |

Source: TÜİK, ibid.

While, in general, Turkeys trade volume with all countries in TRACECA is

increasing, its exports are lower than the exports of member countries except

for Armenia (2011-12), Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan, and Moldova (pls. see

Table 5). Thus, TRACECA is also expected to result in a gradual increase in the

export capability of Turkey.

Table 6: Foreign Trade of

Turkey with the NSR-NDN Countries (1996-2012) (000 $)

|

Countries |

|

1996 |

2000 |

2005 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

|

Afghanistan |

E |

2,114 |

8,053 |

113,401 |

259,791 |

275,969 |

289,915 |

|

I |

224 |

497 |

8,301 |

5,098 |

4,795 |

6,461 |

|

|

India |

E |

59,390 |

56,047 |

219,869 |

606,081 |

756,082 |

791,720 |

|

I |

258,174 |

449,307 |

1,280,473 |

3,409,938 |

6,498,651 |

5,843,638 |

|

|

Kazakhstan |

E |

164,044 |

118,701 |

459,946 |

818,900 |

947,822 |

1,068,625 |

|

I |

100,595 |

346,376 |

558,900 |

1,392,528 |

1,995,115 |

2,056,086 |

|

|

Kyrgyzstan |

E |

47,100 |

20,572 |

89,529 |

129,902 |

180,241 |

257,470 |

|

I |

5,879 |

2,350 |

14,113 |

30,900 |

52,123 |

45,226 |

|

|

Latvia |

E |

1,970 |

16,086 |

81,390 |

65,958 |

115,955 |

127,367 |

|

I |

3,426 |

11,950 |

2,622 |

71,360 |

129,787 |

160,296 |

|

|

Pakistan |

E |

77,875 |

52,857 |

187,554 |

248,147 |

213,672 |

276,127 |

|

I |

83,467 |

82,232 |

315,463 |

749,931 |

873,131 |

555,012 |

|

|

Russia |

E |

1,511,634 |

643,903 |

2,377,050 |

4,628,153 |

5,992,633 |

6,680,777 |

|

I |

1,921,139 |

3,886,583 |

12,905,620 |

21,600,641 |

23,952,914 |

26,625,286 |

|

|

Tajikistan |

E |

4,444 |

4,467 |

46,717 |

143,890 |

172,575 |

234,947 |

|

I |

2,786 |

16,511 |

47,309 |

283,689 |

324,283 |

345,178 |

|

|

Turkmenistan |

E |

65,657 |

120,155 |

180,635 |

1,139,825 |

1,493,336 |

1,480,052 |

|

I |

100,314 |

97,878 |

160,744 |

386,342 |

392,712 |

303,507 |

|

|

Uzbekistan |

E |

230,492 |

82,647 |

151,071 |

282,666 |

354,490 |

449,884 |

|

I |

58,054 |

85,794 |

261,466 |

861,373 |

939,882 |

813,287 |

Source: TÜİK, ibid.

Turkey shows a tendency towards an increase in its foreign trade with the countries

involved in the NSR-NDN too. In this group only Afghanistan, Kyrgyzstan, and

Turkmenistan export less than Turkey (pls. see Table 6). Realization of this

project is also expected to be a factor towards increasing Turkeys trade

relations with these countries particularly with regard to increasing its

export volume.

Conclusion

As the oldest and longest trading route in the world the Historic Silk

Road, established in the second century B.C., extended across continents,

oceans, and seas. While goods and commodities, initially inclusive of silk,

traded over these routes; inventions, devices, techniques, people, cultures,

and religions also moved along the Road. Experiencing its heydays during the

7th-8th and 13th-14th centuries A.D. its significance diminished, and by the

late 17th century it fell into relative disuse as a result of the exploration

of new sea routes and the rise of related transportation facilities. If

considered from the beginning of its existence in the 2nd century B.C. up to

the late 17th century, the total number of countries involved in the Historic

Silk Road -inclusive of its secondary connections in terms of land and sea

routes- are the following: Land routes: China, Kyrgyzstan, Kazakhstan,

Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Bhutan, Nepal,

India, Iran, Iraq, Syria, Russia, Azerbaijan, Georgia, Armenia, and Turkey; Sea

routes: China, Viet Nam, Cambodia, Malaysia, Indonesia, East Timor, Myanmar,

Bangladesh, India, Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Oman, Yemen, Somalia, Kenya, Tanzania,

Djibouti, Eritrea, Sudan, Egypt, Lebanon, Israel, Palestine, Jordan, Syria,

Turkey, Bulgaria, Greece, and Italy; a total, in todays terms, of some 43

countries/territories along both routes.

The Historic Silk Roads are being revitalised following the exploration for

oil and natural gas reserves, in the Middle East, the Caucasus, and the Central

Asian regions in particular. Resulting from these explorations, new areas of

conflict have arisen among nations, and the attention of most of the world is

now focused on this part of the globe. In the 19th century such conflicts were

thought of as the Great Game and from then on many international initiatives,

with particular emphasis given to the regions oil and natural gas reserves but

including weaponry and infrastructural activities, have been centred here.

Among the major international initiatives dealing with oil-natural gas-weapon

transportation and infrastructural services are; Oil Pipeline Projects (OPP),

Natural Gas Pipeline Projects (NGPP), Transport Corridor Europe Caucasus Asia

(TRACECA), Northern Distribution Network (NSR-NDN), Trans-Korean Railroad with

the Trans-Siberian Railroad (TKR-TSR), and the Gulf-Asia Model. Described as

the New Silk Roads. In this context, the names of the initiatives could be read

as; the Asian Silk Road (OPP-NGPP), the European Silk Road (TRACECA), the

American Silk Road (NSR-NDN), the Korean-Russian Silk Road (TKR-TSR; Iron Silk

Road), and the Gulfian Silk Road (the Gulf-Asia Model). While China and the Central

Asian countries were among the main actors on the Historic Silk Road, many more

countries are involved in the New Silk Road projects. Turkey is engaged in the

majority of such initiatives (i.e. OPP, NGPP, TRACECA, and the NSR-NDN) in

terms of their economic and political aspects.

In this paper, the impacts of the New Silk Roads on the foreign trade of

Turkey are discussed. For this purpose, two international COPPs, one of which

is with Iraq, the other with Azerbaijan and Georgia, are taken into account.

According to BOTAŞ statistics there was an upward trend in the transportation

of crude oil from 2007-11: In the latter year this amounted to 163,276,000 bl. As of 2013 Turkey also became involved in the

following international NGPPs: Turkey-Greece-Italy NGPP (ITGI),

Turkey-Bulgaria-Romania-Hungary-Austria NGPP (NABUCCO), Trans-Anatolian NGPP

(TANAP), Iraq-Turkey NGPP, Trans-Caspian Turkmenistan-Turkey-Europe NGPP. When

these projects are completed, the foreign trade of Turkey is also expected to

increase gradually. In the context of the New Silk Roads in line with the Historic Silk Road

routes, the projects in which Turkey has role include the following countries:

COPP: Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iraq; NGPP: Austria,

Azerbaijan, Bulgaria, Greece, Hungary, Iraq, Italy, Romania, Turkmenistan; TRACECA: Armenia, Azerbaijan,

Bulgaria, Georgia, Iran, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Moldova, Romania, Tajikistan,

Ukraine, Uzbekistan; The NSR-NDN: Afghanistan, India, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan,

Latvia, Pakistan, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan.

An analysis of Turkeys data on its foreign trade with the above-mentioned

countries shows that between 1996 and 2012 the trend was upward for both export

and import volumes. The data indicate that Turkey is currently increasing its

foreign trade with all countries involved in the New Silk Road projects.

Moreover, considering their potential Turkey is expected to raise its exports

to these countries to above its imports from them. It can be projected that

completion of such international projects will provide Turkey with many

economic and political advantages greater than those described above. Thus, the

New Silk Roads will increase the trading capacity of Turkey in addition to opening up other economic and political

advantages, just as the Historic Silk Road did.

* Assist. Prof. Dr. Mehmet Behzat Ekinci

Economics, FEAS, Mardin Artuklu University.

** The Silk Roads from the Past to the Future and Their Interactions with

the Foreign Trade of Turkey, Avrasya Etüdleri, Issue: 45, TİKA, Ankara, 2014,

7-42.

Bibliography

Akiner, Shirin. Silk Roads, Great Games and Central

Asia, Asian Affairs, 2011, 42:3,

391-402.

Başyurt, Erhan. Hindistan, İpekyolunu arıyor, Aksiyon, 15.02.1997, http://www.aksiyon.com.tr/aksiyon/haber-2277-32-hindistan-ipekyolunu-ariyor.html, Retrieval

date: 27.05.2013.

Blank, Stephen. Economics and security in Northeast

Asia: The iron silk road, its context and implications, Global Economic Review: Perspectives on East Asian Economies and

Industries, 2002, 31:3, 3-24.

BOTAŞ. Annual

Report, 2011, Ankara, 29.

BOTAŞ. International Projects, http://www.botas.gov.tr/index.asp, Retrieval date:

28.08.2013.

Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook;

Armenia, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/am.html, Retrieval

date: 06.09.2013.

Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook;

Azerbaijan, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/aj.html, Retrieval

date: 06.09.2013.

Central Intelligence Agency, The World Factbook;

Georgia, https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/gg.html, Retrieval

date: 06.09.2013.

Davutoğlu, Ahmet. Beşinci Büyükelçiler Konferansı,

İzmir Üniversiteler Platformu, 05.01.2013, İzmir, http://www.mfa.gov.tr/disisleri-bakani-sayin-ahmet-davutoglu_nun-besinci-buyukelciler-konferansi-kapsaminda-izmir-universiteler-platformu-tarafindan-d.tr.mfa, Retrieval

date: 27.05.2013.

Demir, İdris. Revival of the Silk Road in Terms of

Energy Trade, Gaziantep Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi, 2010, 9:3,

513-514, 513-532.

Hichok, Michael Robert. The other end of the Silk

Road: Japan's Eurasian initiative, Central

Asian Survey, 2000, 19:1, 17-39.

IISS. Still quite narrow: the GulfAsia 'new Silk

Road', Strategic Comments, 2011,

17:9, 1-3.

İsayev, Elbrus and Mustafa Özdemir. Büyük İpek Yolu

ve Türk Dünyası (The Great Silk Road and Turkish World), Zeitschrift für die Welt der Türken, 2011, 3:1, 111-120.

Kaynak, Muhteşem. Ulaştırmada Yeni Eğilimler ve

Türkiyenin Bölgesel Lojistik Güç Olma Potansiyeli, Avrasya Etüdleri, 2003, 3-18.

Kim, Younkyoo and Fabio Indeo. The new great game in

Central Asia post 2014: The US New Silk Road strategy and Sino-Russian

rivalry, Communist and Post-Communist

Studies, 2013, 46, 275-286.

Kuchins, Andrew C.; Thomas M. Sanderson and David A.

Gordon. Afghanistan: Building the Missing Link in the Modern Silk Road, The Washington Quarterly, 2010, 33:2,

33-47.

Leonard, Karen. The Silk Road Renewed? South Asian

Entrepreneurs in Uzbekistan, South Asia:

Journal of South Asian Studies, 2010, 33:2, 276-289.

Major, John. Silk Road: Spreading Ideas and

Innovations, http://asiasociety.org/countries/trade-exchange/silk-road-spreading-ideas-and-innovations, Retrieval

date: 10.07.2013.

Nurhan, Aydın. Ekonomik Küreselleşme ve Türkiye, http://www.mfa.gov.tr/ekonomik-kuresellesme-ve-turkiye-.tr.mfa, Retrieval

date: 27.05.2013.

Toniolo, Lucia; Alfonsina D'Amato; Riccardo Saccenti;

Davide Gulotta and Pier Giorgio Righetti. The Silk Road, Marco Polo, a bible

and its proteome: A detective story, Journal

of Proteomics, 2012, 7:5, 3365-3373.

TRACECA. The Silk Road of the 21st century, http://www.traceca-org.org/en/home/the-silk-road-of-the-21st-century, Retrieval

date: 27.08.2013.

TÜİK (Statistical Institute of Turkey). Main

Statistics; Foreign Trade, http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/UstMenu.do?metod=temelist, Retrieval

date: 30.08.2013.